If you can’t block them, read them.

That line has been around forever, but it’s the foundation of every good RPO system.

The three coaches in today’s breakdown build their RPO game from the same starting point: the box. They count it, they ID it, and they design their reads around what the defense is giving them.

Joe Morehead lays out the philosophy—why you read a defender and what you’re actually trying to accomplish. Elliot Wratten shows how that ID process works in real time against a defense that’s outnumbering you. And Brent Dearmon takes it a step further, explaining how to apply RPO principles to gap schemes where the math gets complicated.

Different levels of detail, same underlying principle: the box tells you what to do.

Joe Morehead: The Philosophy Behind Reading Defenders

Video: Reasons to Read Defenders and Create Conflict

Joe Morehead starts with the fundamental question every RPO system needs to answer: why are you reading a defender in the first place?

He breaks it down into four reasons.

1. Numbers: You’re reading a defender to create numbers at the point of attack when you’re equal in the box or up one. The read allows you to play with an extra gap without having to block it.

2. Angles: Reading a defender gives your offensive linemen better blocking angles. Instead of asking a guy to make a block he can’t make, you remove that defender from the equation and let your linemen work on the guys they can handle.

3. Grass: Morehead calls this getting your athletes into open space—or into matchups they’re likely to win. The read creates opportunities for playmakers to operate where the defense isn’t.

4. Matchups: This is where Morehead references a line from Paul Pascalone at UConn: don’t let the game wreckers wreck the game. Every week you go into the scouting report and identify guys your players can’t block. So don’t block them. Read them.

The staff philosophy is straightforward: never ask your players to do something they’re not mentally or physically capable of doing. If your left tackle can’t block the left defensive end, don’t block him—read him. If you can’t get across to the linebacker, don’t try. Build the read around the problem.

That’s the framework. Now the question becomes: how do you know when the box is telling you to throw?

Elliot Wratten: IDing the Box and Knowing When to Throw

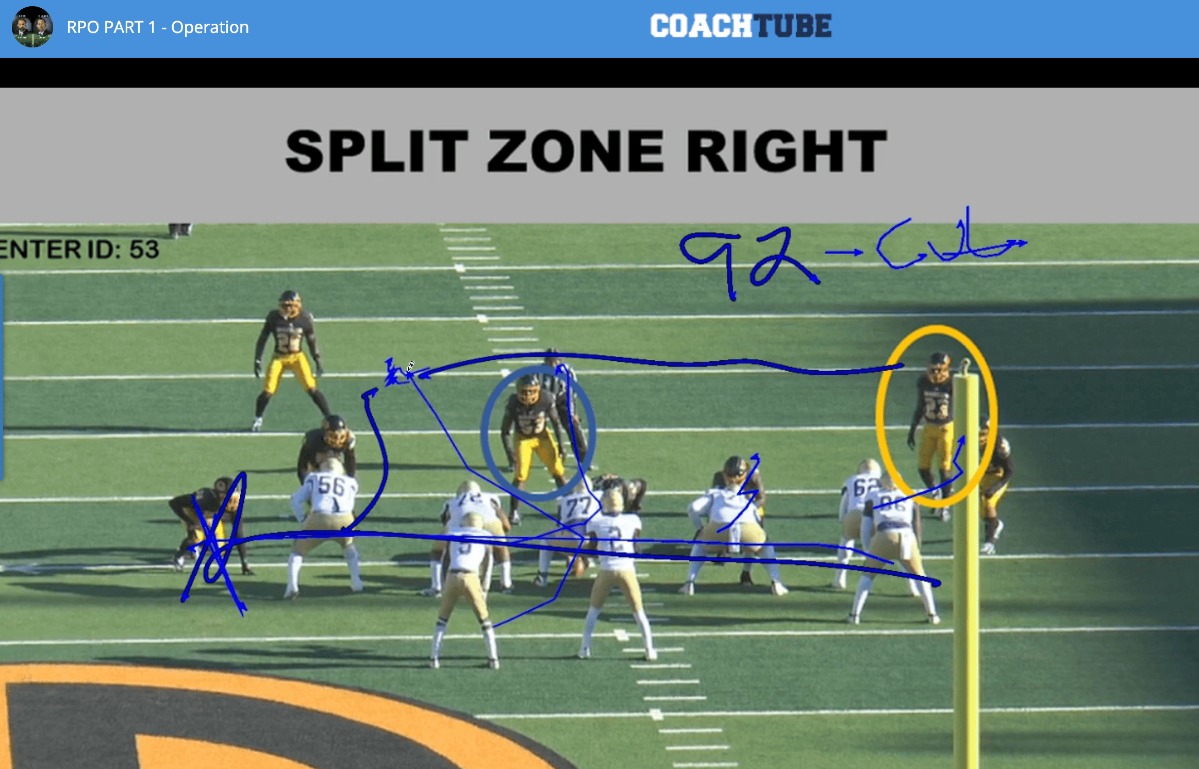

Elliot Wratten shows what this looks like against a defense that’s doing everything it can to outnumber you in the box.

The example is a five-down look—not the clean 4-2 over front everybody loves to diagram. Defenses are evolving, and they’re going to stress your numbers every way they can.

In this look, the center comes up and they’re essentially manned across the front. He IDs the mike—53 in this case. Tackles are out, the scoop-stack responsibilities are covered.

But here’s where the box count matters.

The defense is playing a single-high structure and rotating a safety down into the fit. Wratten points out that when that safety is playing at four yards, he might as well be a linebacker. The defense is adding a hat to the box without showing it in a traditional alignment.

That’s telling the offense one thing: the ball needs to be thrown.

It’s not complicated. You work your ID, you count the box, and when the numbers say throw, you throw. The offense adjusts their point every week based on what the defense is doing, but the process stays the same.

When a safety is sitting at four yards waiting to play run first, the RPO gives you the answer. You’re not going to win at the point of attack, so you take the throw and make the defense pay for loading the box.

This is what Morehead was talking about. Don’t ask your guys to do something they can’t do. When the box tells you to throw, throw.

But what happens when you get into gap schemes? The math changes. And that’s where the quarterback needs solid answers.

Brent Dearmon: Gap Scheme RPOs and the Backside Problem

Brent Dearmon addresses the question that makes coaches nervous about gap scheme RPOs: what happens to the backside gaps when you pull a lineman?

He starts with the contrast. Inside zone is the easiest way to do RPOs because there’s no interior gap problem. Everybody’s working in the same direction, and the blocking scheme doesn’t create holes behind it.

Power is different.

Dearmon explains it simply: when you run power, you’re taking a backside gap and adding it to the front side. You pull the backside guard to the play side, which means you took a gap from one side and moved it to the other.

That’s fine for the run game. But it creates a problem for RPOs.

You’re asking the center to block A gap to B gap. You’re asking the tackle to block B gap, hinge, and get back to C gap. And as Dearmon puts it—referencing Matthew 6—you can’t serve two masters. There’s no way both of those guys can cover two different gaps if the defense sends pressure to the vacated side.

So his quarterbacks have to understand the hot gap.

On every power RPO diagram he hands out, there’s an arrow pointing to the backside gap that says “hot gap.” If the defense brings any pressure to the gap the hinge player can’t cover, the quarterback is not throwing a late RPO. He’s giving the ball and getting out of the way or else he’s going to get hit in the back.

But the scheme still gives the offense answers.

Pre-snap, the quarterback looks at the boundary. If the boundary safety is tight to the fit, the single receiver has an expanded hitch or the quarterback can give him any quick game he wants (slant, speed out, fade). This is fixing the D gap before the snap.

Dearmon does emphasize that this is optional. Do you have to throw a five-yard hitch? He’d rather have a seven-yard downhill power run than a five-yard catch. The boundary throw is there to fix the D gap if the defense is cheating to take it away, not as a first option.

Post-snap, the read moves to the play side. If the Sam linebacker triggers downhill and gets in the fit during the ride, the quarterback pulls it and throws the two-receiver screen to the field. The Z takes two steps and comes back down the stem. The Y is protecting for the screen, blocking whoever triggers the throw, usually the corner.

This is an off-coverage concept. Dearmon wants to attack whoever’s giving off coverage with his RPO. Against man, they have built-in answers and will likely check to a different play.

The key to all of it is the quarterback’s understanding of what’s happening on the backside. Gap schemes create vulnerability. The RPO reads have to account for it.

So — three coaches, one framework.

Morehead gives you the philosophy: read defenders to create numbers, angles, grass, and matchups, and never ask your players to do something they can’t do.

Wratten shows you the ID process in action: count the box, recognize when the defense is loading it, and throw when the numbers tell you to.

Dearmon takes it into gap schemes: understand the backside problem, teach the hot gap, and build pre-snap and post-snap answers that account for where you’re vulnerable.

The box tells you what to do. Your job is to make sure your quarterbacks can read it.