The Seattle Seahawks won Super Bowl XLVIII by smothering the Patriots’ passing attack. That dominant secondary performance didn’t come from one coverage. It came from a system where every defender knew exactly which tool to use based on what the offense showed them.

Chris Partridge, OLBs Coach for the Seattle Seahawks, teaches a bracket coverage system built on that same principle: read the formation first, then select your tool.

The First Read: Condensed vs. Non-Condensed

Before his players think about leverage or technique, Partridge wants them answering one question: am I facing a condensed formation or a non-condensed formation?

This matters because the tools change. Non-condensed splits give you space to work with. Your underneath defenders can play with more cushion, and your brackets operate with cleaner sight lines. Condensed splits compress everything. Receivers are within four yards of each other, and your coverage rules need to account for that tightness.

Partridge teaches this as the entry point to the entire system. Get this read wrong and you’re pulling from the wrong toolbox.

Non-Condensed Formations: Ace, Indy, and Ohio

Once players identify a non-condensed set, they have three primary bracket calls. The safety makes the call to each side based on the receiver alignment.

Ace: Single Receiver (X or Flanker)

Against a tight end with a flanker or a single X receiver, the call is Ace.

The corner plays outside leverage man. He wants to get hands on at the line. The safety plays with depth and peeks the release. Partridge emphasizes that the safety is a pass-run player here—he’s not locked on the receiver, he’s reading.

If the receiver releases outside, the safety’s eyes go back inside. If the receiver releases inside, the safety stays on him. An inside release means the safety is now responsible for that route—whether it’s a shallow or a post, he’s matching it.

Partridge stresses one coaching point repeatedly: keep your shoulders square as long as possible. Safeties see an inside vertical release and want to turn their shoulders to match it. That’s when a dig gets banged inside of them. Stay square, give ground only when you get a speed release straight at you, and only turn your shoulders when you’re committing to double a vertical.

Indy: Slot Receiver, Inside Leverage Bracket

When the offense shows twins, doubles, or any slot alignment, Partridge moves to either Indy or Ohio. The call tells the safety where his leverage is.

Indy puts the double team on the slot receiver from the inside. The low defender—Partridge calls this position the star, but it could be your nickel, your SAM, or whoever matches up best—plays catch man technique. If the slot releases vertical straight at him, he collisions and plays catch man on the route.

The safety aligns at 10 yards (adjusted for red zone or down-and-distance) and plays the same bracket principles: any inside release on the slot is his responsibility. He takes the in-cut, the shallow, or the post.

The coaching point is the same: shoulders square as long as possible. Only give ground against a vertical speed release.

Ohio: Slot Receiver, Outside Leverage Bracket

Ohio flips the leverage. Now the star plays inside, aligned in the apex. The safety has outside leverage on the slot.

Because the star has high-outside help from the safety, Partridge allows him to get his eyes inside. This makes Ohio a better call in run-heavy situations—the star can function as the overhang defender while still being part of the bracket.

The safety takes any out-cut. Same technique, opposite leverage.

Partridge notes that Ohio is easier to disguise than Indy. You can press the star and bail him inside. The safety can come down and show man before getting to his landmark. There’s more room for “show bracket”—giving the quarterback different looks pre-snap while still executing the same coverage post-snap.

One additional detail for the star on Ohio: if the slot runs a vertical and bends inside, the star man-turns that bender. You don’t zone-turn it and let the route get behind you, because the safety’s outside leverage makes it harder for him to cover an in-cut from that position. Man-turn the bender, stay on the route.

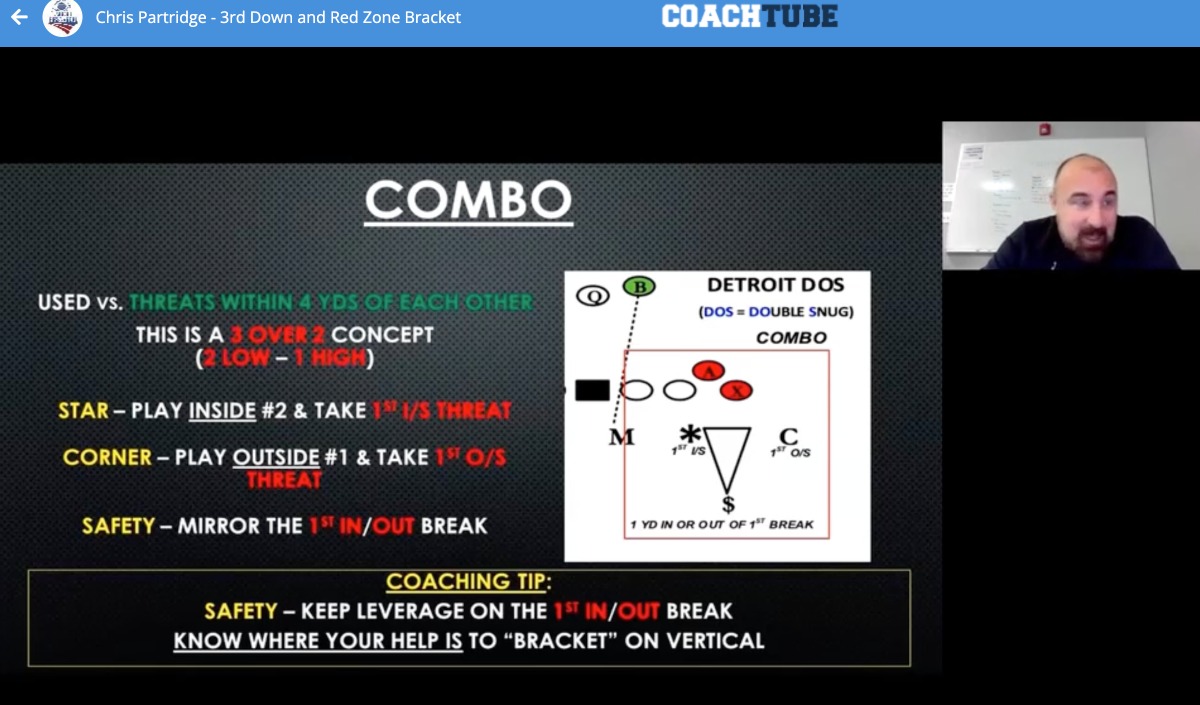

Condensed Formations: Combo Coverage

When receivers condense their splits—common on third down and in the red zone—the non-condensed tools don’t apply cleanly. Partridge moves to Combo.

Combo is a 3-over-2 concept: two low defenders and one high. The safety stays on top while the two underneath players—corner and star, or corner and Mike, depending on personnel—bracket the condensed receivers.

The rule is first-break.

The star takes the first inside break. The corner takes the first outside break. The safety reads which direction the first break goes and slides to double from the opposite side.

Here’s how it plays out: if the slot (let’s call him the A receiver) breaks inside, the star takes him. The safety now knows his double comes from the outside—he and the corner are bracketing the X. If the A breaks outside, the corner takes him, and the safety slides inside because his double now comes from the star’s side.

Partridge is clear that this is a rep deal. You can’t install Combo once and expect clean execution. Players need to walk through the first-break reads repeatedly until the reactions are automatic.

He also gives a usage guideline: Combo works when the threats are within four yards of each other. That’s your condensed indicator. Once splits widen past that, you’re back to your non-condensed tools.

The system Partridge teaches is built on one principle: the formation tells you which tool to use. Condensed or non-condensed is the first filter. From there, the specific alignment—single receiver, slot inside, slot outside, compressed splits—dictates the call.

The technique details stay consistent across all of it. Shoulders square. Read the release. Know who has inside responsibility and who has outside responsibility. The only thing changing is the leverage, and that’s determined before the snap.