Play-action works when it punishes how the defense plays the run. The problem is that most play-action concepts ask you to sacrifice something—either protection or the quality of the fake.

The two coaches in this week’s breakdown don’t accept that trade-off. They’ve built play-action systems that keep the quarterback clean while attacking specific defensive reactions.

Mercer’s staff influences play-side run support with a gap protection scheme that lets the back sell hard and release. Josh Herring uses orbit motion to stress secondary communication and uncap coverages.

Different mechanisms, same principle: make the defense wrong for how they’re fitting your run game.

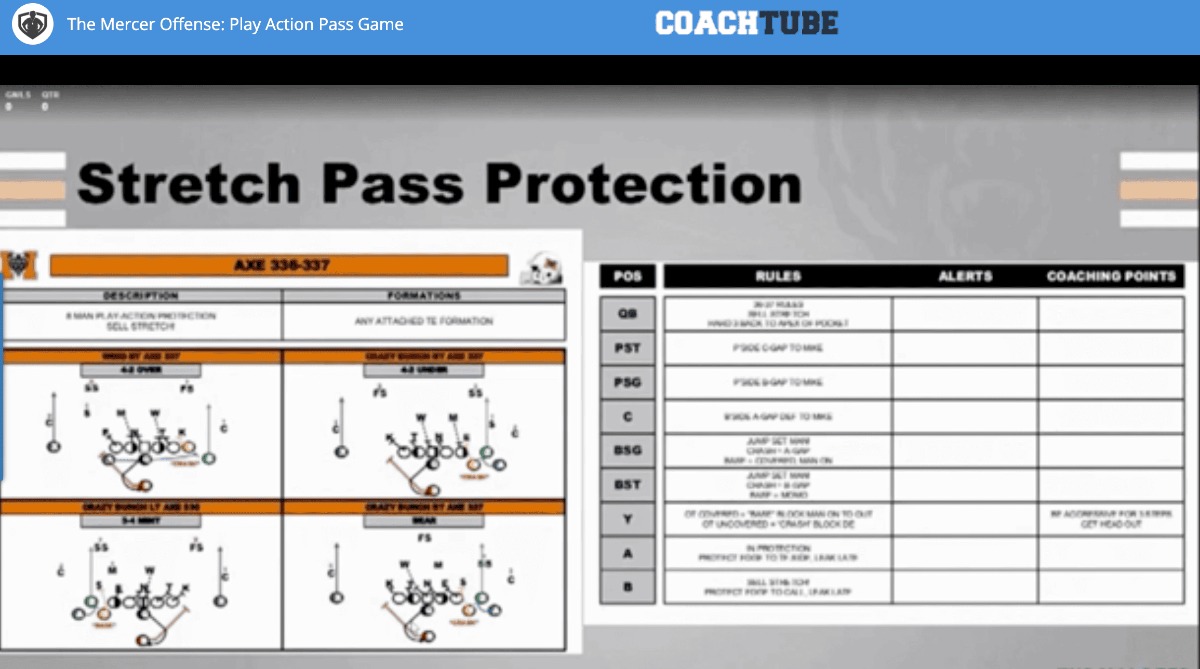

Mercer’s Stretch Pass Protection: Hard Run Action That Actually Protects

Mercer’s play-action game starts with a simple question: how do you influence play-side run support without giving up the backside?

Their answer is stretch pass protection—a gap scheme that lets them run hard fakes while keeping the quarterback clean.

The offensive line gap protects. The back sells the stretch hard—this isn’t a lazy play-fake. The tight end handles backside protection.

And there’s always another body (second tight end or A-back) who has the linebacker to the first guy outside. That extra protector picks up weak corner fire, but if there’s no pressure, he’s releasing to the flat.

The quarterback depth is specific: seven-and-a-half to eight-and-a-half yards, approximately at the original alignment of the center.

He’s not rolling out. He’s not bootlegging. He’s pulling up in the pocket after the hard run action.

The Mercer staff emphasizes that this depth gives the tackles license to be aggressive—they’ve got help from both sides with the back and the extra protector.

The distinction from naked matters. The staff explains that naked is for controlling the backside—fake stretch one way, boot the other, let the action hold the backside end and linebacker.

Stretch pass protection is for influencing play-side run support. The defense is fitting the run. They’re flying to their gaps.

RPOs push the ball a little bit, but when Mercer wants to push it further downfield, this is what they go to.

The primary target is a big post attacking where the safety vacated to fit the run. The back continues to the flat, dragging the near defender (corner or safety) out of the throwing window.

The staff varies the presentation throughout the season—sometimes a sail route where the receiver pushes to 12-15 yards and breaks back outside, sometimes a deep whip to flatten it out.

The quarterback reads the same area regardless. What changes is who’s running into it.

On the back’s release, the Mercer staff is adamant: he should be breaking a rib on his way out to the flat. That’s a free shot on any defender trying to jet upfield and stop the play.

Early in their install, backs stayed in too long because they didn’t trust the O-line. The staff stresses that this kills the concept.

Once a lineman engages his man, he’s married until the whistle—the back has to get out and drag someone with him.

The motion man can also serve as the extra protector, checking the linebacker before releasing if nothing comes.

One more detail from the clinic: the staff tells their O-line which side the fake is going so they can sell the hard run action better. However you communicate it, that information helps the line commit to the look.

Josh Herring’s Half-Roll Series: Using Orbit Motion to Uncap Coverages

Josh Herring runs a half-roll play-action concept that attacks defenses through communication stress.

Where Mercer influences run fits, Herring creates problems in how the secondary talks to each other.

The structure: half-roll action (about five steps), pulling guard, and orbit motion from an outside receiver crossing the formation.

Herring explains that the motion does three things simultaneously. It threatens the fast screen they run off the same look—something he’s covered in other clinics. It mirrors their gap scheme runs (power, counter). And it forces the secondary to make a call about who’s responsible for what.

To this point, he says, the defense shouldn’t have any idea whether it’s a run, a screen, or play-action.

The route concept is a three-level read that Herring calls ride, burp, flat.

The ride route attacks the hash—the X receiver (outside receiver to the play-action side) works across and rides out. The burp is a backside inside-release post—if the receiver can get an inside release, he’s running it. The flat is the orbit man if nothing else opens up.

Herring walks through exactly how the coverage manipulation works. The safety has to make a quick decision.

When defenses cloud quickly to handle the orbit motion, the corner takes the flat guy—and that uncaps the ride route. The deep-half safety gets caught weaving too wide, and the quarterback throws over him.

When the safety stays deep and plays soft, nobody takes the flat. Easy completion, let the orbit man run after the catch.

He shows the same results from multiple presentations. Sometimes the orbit comes from the slot instead of the outside receiver.

Sometimes they run it from a two-back set with a sniffer and a flexed tight end—the same look they use for their gap scheme runs and screens. The motion can come from the backfield in that set.

In one clip in the clinic, the strong safety takes the motion so aggressively that the defense completely loses the burp. The quarterback steps up, works back to him, and it goes for a long touchdown.

On protection, Herring adjusts to the front. Against an even front, the tight end steps down even if nobody’s there—he can give a hand and help double before working to the second level.

The guard pulls for the defensive end. If the end gets width instead of squeezing, the guard picks him up. The backside tackle straight-sets his man. The running back finds work, picking up any edge blitzer off the backside.

Herring also addresses the quarterback’s footwork. If the quarterback feels pressure and needs to get rid of it quicker, he doesn’t have to turn his shoulders—he can slide immediately into his drop.

As long as he maintains balance, Herring is fine with that adjustment. The read stays clean: high, medium, low. Find who’s uncapped and throw the touchdown.

One coaching point on the ride route: Herring wants the receiver wider on his split, running right up the hash area.

In one clip, the receiver scoots inside and it makes the backside safety a factor. They live with it, but the preference is clear—wider split keeps the throwing lane clean.

Two different approaches to play-action, but the same underlying idea: attack the defense for how they’re playing your run game.

Mercer’s stretch pass protection punishes aggressive run fits by attacking where the safety vacates. Herring’s orbit motion forces communication and creates openings when the secondary has to make quick decisions.

Both keep the quarterback protected. Both give your receivers chances to win without beating man coverage. And both tie directly to run concepts you’re already teaching.